Support and Maintenance for our Orthopaedic Patients

Orthopaedic disorders are very common and cover a wide range of different conditions.

From Osteoarthritis and Spondylosis, to Elbow and Hip dysplasia, Orthopaedic disorders affect both young and old, and most dogs will develop one or another within their lifetime.

Clinical Canine Massage is a results-driven, remedial therapy which helps to support these Orthopaedic conditions, and commonly keeps dogs moving for longer, manages their pain, and improves their quality of life. If you’d like to find out more, or discuss your own dog, please do get in touch.

The Orthopaedic Patient

Dogs can suffer from a range of different Orthopaedic disorders, the most common of which include Osteoarthritis, Spondylosis, Elbow and Hip Dysplasia, Luxating Patella, Cruciate Ligament Rupture, and Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD).

Unlike a lot of muscular and soft tissue issues which tend to be acute and can be rehabilitated with time, Orthopaedic conditions are often ongoing, chronic disorders that require careful management and support. Conservative measures include adaptations to activities of daily living, complementary therapies, and pain management, but sometimes surgical intervention will also be required.

If your dog has been diagnosed with one of these Orthopaedic conditions, or you’d just like to know what signs and symptoms to look out for, take a look below where you’ll find a brief description of each disorder along with how Clinical Canine Massage can help in each case.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis, or degenerative joint disease, is a chronic form of joint inflammation caused by a progressive and permanent long-term deterioration of the cartilage surrounding the joints. As cartilage ages, it begins to wear down with areas of roughened and softened surface, and as the edge of the joint thickens, bony spurs are formed and the joint begins to swell as extra synovial fluid is produced. In an attempt to overcompensate for this swelling, the joint capsule and ligaments begin to change shape, thickening and contracting. Ultimately, cartilage is unable to repair itself to the extent that is required and in severe cases, cartilage can become so thin that the bones begin to rub against one another and gradually wear each other down, leading to pain and deformation of the joint.

Symptoms of Osteoarthritis

- Varying degrees of lameness

- Difficulty getting up after rest

- Difficulty going up and down the stairs

- Reduced mobility and range of motion

- Generally slowing down and stiffness

- Inability or reluctance to jump

- Difficulty urinating and defecating

- Reluctance to exercise

- Fluid on the joint

- Muscle wastage around the affected joint

- Lick granuloma/nibbling over the affected site

- Loss of proprioception

- Crepitus or creaking of the joints

- Increased pain in humid and cold weather

- Low mood or anxiety

- Loss of appetite

- Disturbed sleep or restlessness

Benefits of Clinical Canine Massage

- Improves mobility and range of motion

- Addresses hypertonic muscles

- Addresses muscles that become fixed into habitual patterns

- Relieves areas of muscular overcompensation

- Enables a return to activities of daily living previously stopped

- Improves ability to exercise

- Breaks the pain-tension-pain cycle

- Reduces inflammation or fluid over the joint

- Improves pain management

- Promotes a happier dog

- Improves appetite

Spondylosis

Spondylosis, also called Ankylosing Spondylitis, is an ageing disease of the intervertebral discs, characterised by the development of bony spurs which on x-rays show as bridge formations on the underside of the vertebrae, with the most commonly affected areas being within the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae (T9-T10 and L2-L4). If the Spondylosis continues to other vertebrae, there may be several of these bridges resulting in the vertebrae becoming less flexible and fusing together. It is commonly thought of as Arthritis of the spine, however unlike Arthritis, Spondylosis is a non-inflammatory condition. Spondylosis begins with the breakdown of the outer portion of the intervertebral discs such that the inner disc material then protrudes, stretching the ligament and in turn encouraging the growth of bony spurs from the vertebral bodies. As a result, pressure is commonly applied to exiting spinal nerve roots which has neurological impacts such as referred pain. Older, large-breed dogs are at highest risk for developing spondylosis and treatment generally involves pain and lifestyle management.

Spondylosis is most commonly associated with ageing but can also develop as a result of repeated microtrauma; major trauma to the back, such as the impact of another dog running into them; the repeated pressure on the same joints or bones as through certain exercises or other activities; and as a secondary issue following intervertebral disc disease or spinal surgery. It may also be more prevalent in dogs who have had abdominal surgery or have excessive scarring following a spay, as the resulting weakening of the abdominal wall puts excessive pressure on the spine as it struggles to stabilise these core muscles. Similarly, dogs with excessive muscular strains (tears) to the muscles that run alongside and stabilise the spine may also develop spondylosis as the vertebrae have to work harder to stabilise themselves.

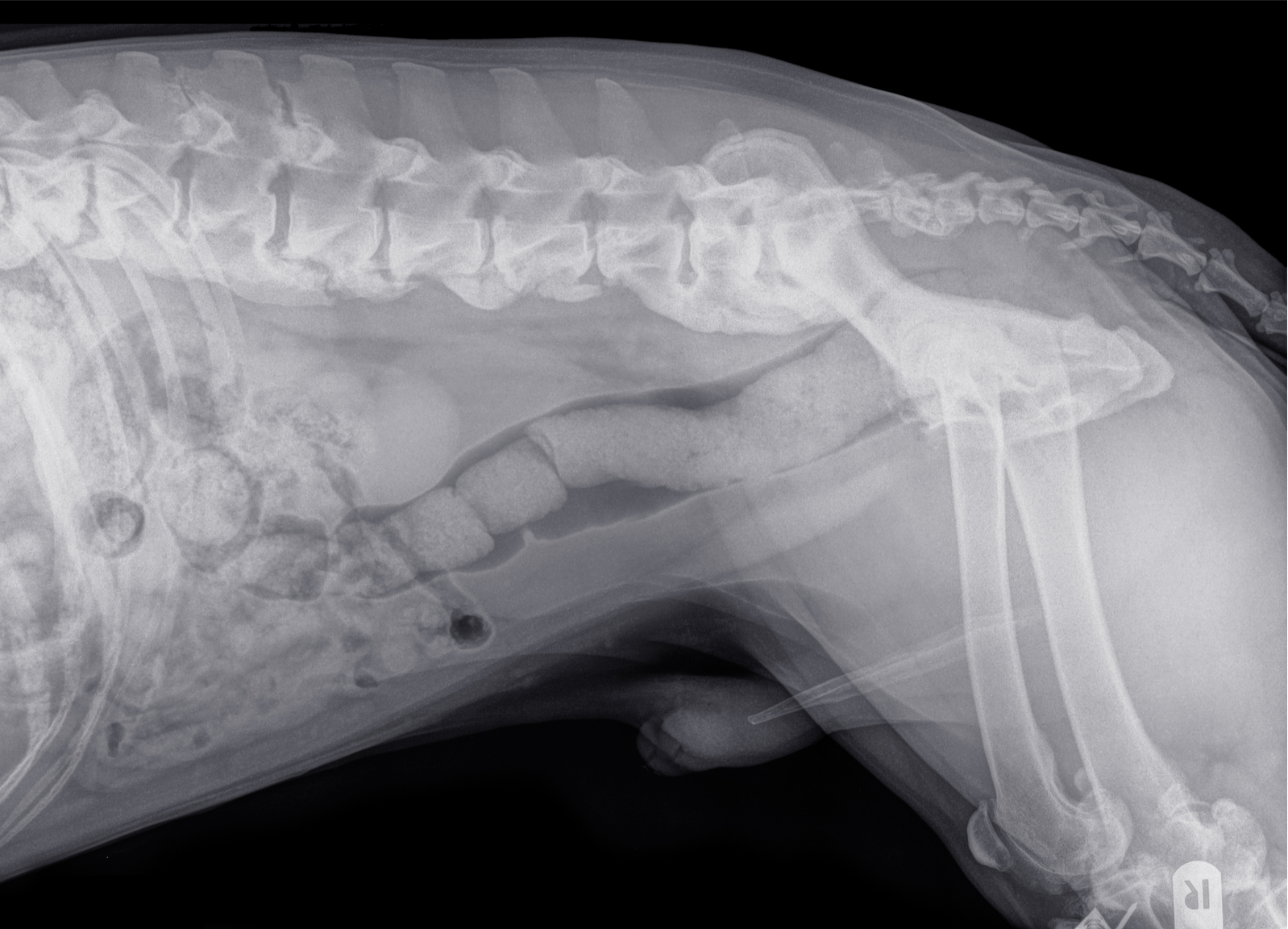

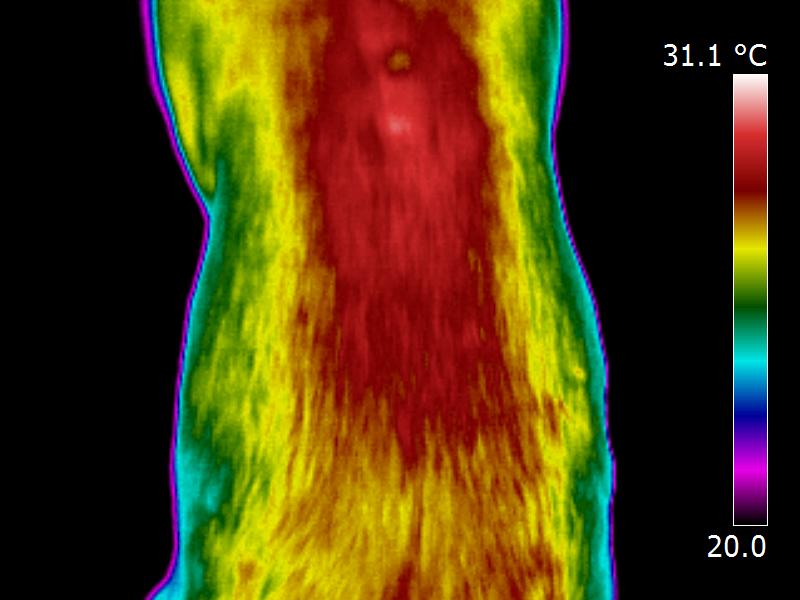

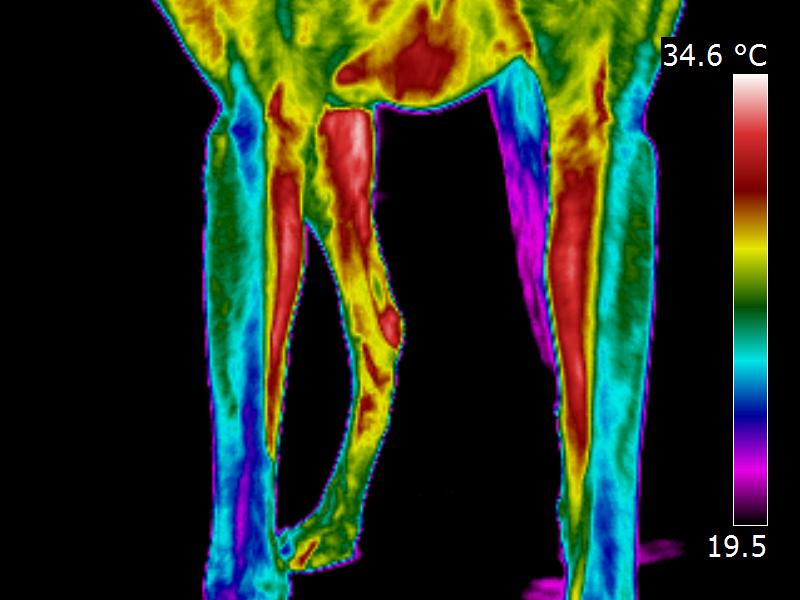

As part of my previous work as a Veterinary Thermographer, I imaged a 10 year old ex-racing Greyhound with clinically undiagnosed extensive back pain. As shown by the two images below, Thermal Imaging identified three problems; firstly, significant localised heat was found overlying spasmic muscle groups, as denoted by the large red area along her back; secondly, highly defined cool spots were observed directly overlying several thoracic vertebrae, which indicated chronic Arthritic type changes; thirdly, the thermal images of her legs showed unusual colour bands called dermatomes which indicated that one or more of the exiting spinal nerve roots was being compressed. A subsequent CT scan diagnosed Spondylosis.

Symptoms of Spondylosis

- Numbness and weakness in the forelimbs

- Nerve deficit and lack of proprioception in the hindlimbs

- Yelping in pain when turning or twisting in a specific direction

- Lameness

- Loss of balance

- Stiffness, loss of flexibility and reduced mobility

- Reluctance to sit

- Roaching of the back – upward curvature of the spine

- Tenderness over the affected area

- Ataxia (loss of coordination) and sometimes paralysis

- Character change – not wanting contact from other dogs

- Neck pain due to stabilising spinal muscles attaching here

Benefits of Canine Massage

- Improves pain management

- Helps to control referred pain due to nerve irritation

- Relieves compensatory muscular tension

- Improves mobility and flexibility by easing surrounding tissue

- Relieves stiffness

- Maintains and increases joint movement

- Helps to improve posture and gait

- Addresses areas of Myofascial pain and Trigger Points

Elbow Dysplasia

Given that the term dysplasia means abnormality of development, Elbow Dysplasia therefore refers to abnormal development of the elbow joint and is the most common cause of forelimb lameness in young large and giant breed dogs. The elbow is a complex joint involving the articulation of three bones; the humerus, radius and ulna. If these three bones do not fit together absolutely perfectly as a result of abnormal development, the consequence is abnormal concentration of forces on a specific part of the joint. And as the joint is subsequently unable to articulate normally, problems in the cartilage and the bones arise. Treatment varies depending on the distinct abnormalities present, with conservative measures including the likes of a low-impact exercise programme, weight management, and medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, whilst surgical intervention often involves the removal of fragmented processes or cartilage flaps if severe.

Elbow Dysplasia is primarily of genetic cause, although environmental factors may influence whether a dog with the genetic coding for Elbow Dysplasia will actually develop a clinical problem. Such environmental factors include over exercise and excessive stair use whilst young, injury to the joint, commencing jumping too early at agility, and poor nutrition and weight management as a puppy.

Symptoms of Elbow Dysplasia

- Foreleg lameness

- Pain

- Abduction of the elbows (out at the elbows) or ‘bow legged’

- Holding the affected leg out from the body whilst walking

- Stiffness, particularly after rest

- Reluctance to exercise

- Difficulty going down the stairs

- Reluctance to jump out of the car

- Reduced range of motion in the elbow joint

- Joint thickening or swelling over the elbow joint

- Flopping to the floor rather than a controlled ‘down’

- Occasionally there will be no clinical symptoms

Benefits of Canine Massage

- Pre-surgical conditioning

- Post-operative rehabilitation

- Relieves compensatory muscular tension and trauma

- Relieves inflammation

- Improves pain management

- Improves mobility

- Maintains or improves range of motion and flexibility

- Relieves muscular spasm and Trigger Points that develop

Hip Dysplasia

Hip Dysplasia is the abnormal developmental of the hip joint. It’s due to a poor coxofemoral joint conformation and is a fairly common problem for all breeds but especially large, fast growing breeds. In basic terms, the ball and socket components of the hip joint do not fit together as snugly as they are supposed to. As a result, the joint becomes unstable, the capsule and teres ligament become stretched, and the articular cartilage becomes eroded. In an attempt to re-establish joint stability, new bone is laid down, which often produces secondary Osteoarthritis when coupled with the cartilage degeneration. Furthermore, the joints can become inflamed if the head of the femur is misshapen, as abnormal wear and tear will occur. Non-surgical treatment options include physical therapies alongside weight management and medication to support cartilage and reduce inflammation, whilst surgical options include Femoral Head Ostectomy (FHO), Triple Osteotomy, and Total Hip Replacement (THR).

Hip Dysplasia is considered to be a multifactorial disease with genetic predisposition, nutrition, trauma, and exercise all influencing the outcome. Essentially, as with Elbow Dysplasia, the inherited component is caused by the presence of certain genetic coding, however the expression of these genes may be modified by environmental factors, all of which will influence how unstable the hip joint becomes and how much secondary Osteoarthritis develops.

Symptoms of Hip Dysplasia

- Hindlimb lameness, particularly after exercise

- Reluctance to run and jump

- Reduced exercise tolerance

- Sitting in a ‘frog’ position with one hip splayed out

- Difficulty utilising stairs

- Pain in and around hip joints

- Difficulty rising from lying or sitting positions

- Bunny Hopping, particularly when going up the stairs

- Pronounced swagger through the hind end

- Stiffness

- Crepitus or creaking in the joint

- Decreased range of motion in the hip joints

- Enlarged shoulder muscles from overcompensation

- Muscle wastage through the hind qaurters

Benefits of Canine Massage

- Pre-surgical conditioning

- Post-operative rehabilitation

- Relieves compensatory muscular tension and trauma

- Relieves inflammation

- Improves pain management

- Improves mobility

- Maintains or improves range of motion and flexibility

- Reduces incidences of lameness

- Enables increased exercise tolerance

- Helps to strengthen muscles

- Improves quality of life

Cruciate Ligament Rupture

Stability in the stifle joint is maintained via four ligaments which cross over each other, providing support, flexibility and movement. The Cranial Cruciate Ligament is a band of tough fibrous tissue that attaches the femur to the tibia, preventing the tibia from shifting forward relative to the femur and preventing the stifle from over-extending or rotating. The cruciate ligaments are susceptible to sprains (tearing or rupture) when overstretched. Sprains vary in severity from a minor tear or stretch, through to a complete rupture, sometimes taking small pieces of bone with it. The more severe, the more painful and debilitating the injury, and often surgical intervention will be required. The most common pathology within the stifle joint is rupture of the Cranial Cruciate Ligament, making the leg weak, lame and unstable. Treatment generally depends upon the severity of the pathology as well as body size and exercise expectations.

In a lot of cases, the cruciate ligament is ruptured as a result of long-term degeneration of the ligament fibres, most likely due to a genetic predisposition, with certain breeds such as Labrador Retrievers, Rottweilers, Boxers, West Highland White Terriers and Newfoundlands being more prone to the condition than others. However, accidental injury also accounts for some incidences of cruciate damage, such as sudden twisting of the knee, use of ball launchers which causes excessive twist or torque to the joint as the dog brakes to retrieve the ball, living on slippy flooring, and stepping down a hole for instance. Additionally, poor weight management, structural abnormality, poor muscle tone, and a history of previous injury or tearing also increases the risk of developing cruciate ligament pathology.

Symptoms of Cruciate Ligament Tear/Rupture

- Subtle to marked intermittent hindleg lameness

- Reluctance or inability to weightbear through the hindlimb

- Crying out in pain

- Inflammation, swelling or heat around the stifle joint

- Stifle held out (abducted) to the side when sitting or standing

- Semi-flexed leg with only the toes on the ground

Benefits of Canine Massage

- Pre-surgical conditioning

- Post-operative rehabilitation

- Relieves compensatory muscular tension and trauma

- Relieves inflammation

- Improves pain management

- Improves mobility

- Encourages equal balance through all four limbs

- Enables more comfortable weightbearing

Luxating Patella

The patella (knee cap) is situated just above the stifle joint and in some dogs, rather than sliding up and down in its stabilising groove on the front of the femur, it will luxate (dislocate) outside of this normal depression. In most cases, when the patella luxates from the groove, it can only be returned to its normal position once the quadriceps muscles relax and the stifle joint is extended (straightened), and it is for this reason that most dogs with the condition will hold up their hind leg for a few minutes before returning to normal activity. The characteristic hop-hop-skip action often seen with this condition is the dog trying to “pop” the patella back into its groove. However, there are four grades of Luxating Patella; Patella luxates and returns to the normal position; Patella luxates when stifle is flexed and remains in this position until the stifle is extended (straightened); Patella is luxated for a majority of the time, can be manually replaced but will luxate again in a short period of time; Permanent luxation where it stays misaligned and will not sit in its groove even for short periods. Luxating Patella can occur in any dog but is most commonly seen in toy and miniature breeds. Surgical intervention is the preferred treatment of choice for severe cases however it cannot offer guaranteed results.

Luxating Patella has a number of causes including past trauma to the stifle, persistent standing on the hindlimbs, genetic predisposition, poor breeding, and malformation of the patella and groove during the growth phase. In the latter three cases, the clinical signs of the condition will normally start to show approximately four months after birth.

Symptoms of Luxating Patella

- Hop-Hop-Skip action

- Intermittent or consistent lameness

- Crying in Pain

- Suddenly pulling up/stopping

- Holding hindlimb up for several minutes before continuing

- Clicking around the stifle joint

- Stiffness or lack of natural movement in the stifle

- Altered gait – bowlegged or walking in a crouch position

Benefits of Canine Massage

- Can realign patella and prevent surgery with Grade 1 cases

- Lengthens the muscles around the area to reduce incidences

- Relieves areas of overcompensation for higher Grades

- Post-operative rehabilitation

- Improves pain management

- Improves mobility

- Improves gait

- Enables return to sensible exercise/activities of daily living

Osteochondritis Dissecans

OCD is a generalised condition which occurs when a piece of cartilage becomes loose or pulls away from the surface of a joint, causing pain and inflammation. It usually occurs during the process of endochondral ossification as the dog is growing and it’s commonly seen in the shoulder, elbow and hock (ankle). Essentially, the cartilage becomes over-thickened, bone formation does not progress normally as the bone marrow cannot penetrate the cartilage, and as a result the cartilage becomes less able to withstand the normal weightbearing forces imposed upon it and becomes necrotic and breaks away from the underlying subchondral bone, either as a flap of cartilage or as an osteochondral fragment (cartlage with bone). Although the offending flap is sometimes reabsorbed back into the system, it quite often remains as a painful fragment, but surgical intervention can be undertaken to remove it.

OCD is caused by the interaction of a number of factors including a genetic predisposition, with the condition most commonly affecting large breed puppies between the age of four and eight months due to their rapid bone development; nutritional deficiency or over-supplementation, particularly with calcium; excessive exercise as a puppy; trauma; harmful activites of daily living such as ball launchers or living on slippy flooring; and hormonal imbalance.

Symptoms of Osteochondritis Dissecans

- Lameness, may be mild initially but worse after exercise

- Uneven weightbearing through the limbs

- Muscular wastage around the affected joints

- Decreased muscle development

- Overcompensating through the unaffected limbs

- Swelling of the affected joints

- Reduced range of motion through the affected joints

- Reduced or restricted mobility

Benefits of Canine Massage

- Pre-surgical conditioning

- Speeds up post-operative rehabilitation

- Relieves areas of compensatory muscular tension

- Relieves painful muscular spasms

- Improves pain management

- Improves mobility

- Encourages equal weightbearing through all four limbs

- Helps to strengthen the affected limb and restore muscle tone

- Flushes away waste cartilage by improving circulation and lymphatics

What next?

If you’re dog has been diagnosed with any of the above Orthopaedic conditions or you’ve been noticing some of the signs and symptoms above, just pop us a message, as Clinical Canine Massage would likely be a great next step. If your dog has yet to be diagnosed with an Orthopaedic disorder, we’d advise you visit your vet for a consultation and clinical assessment initially.

And whats more, the Canine Massage Guild have devised a fantastic consultation aid called The Five Principles of Pain, which you can take with you to your consultation to help you and your vet to assess your dog for the viability of Clinical Canine Massage therapy. It’s likely that if your dog does have an underlying Orthopaedic condition, they will be presenting with a number of clinical and sub-clinical signs of muscular and myofascial pain that are frequently helped by Canine Massage as a result. Click here to download the Five Principles of Pain sheet.

Veterinary Consent

As a member of the Canine Massage Guild, Paw Vida offer a very professional Clinical Canine Massage service and respect the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1966 and Exemption Order 2015 by never working on an animal without gaining prior veterinary approval. In simple terms, this means we’ll only massage your dog if your vet considers it appropriate and safe to do so. Some diseases and conditions are contraindicative to massage and we, or your vet, will of course advise you of this when you get in touch.

You can download our Veterinary Consent form here. Please note that without veterinary consent, we’ll be unable to massage your dog.

Prices

Initial consultation and Treatment

£45.00*

Follow up / Maintenance Treatments

£40.00*

* A small additional travel charge may apply depending on your location.

Canine Massage Clinic packages are also available for training clubs and groups. Please contact us to discuss your requirements.

A big thank you to my Lexi and my picture perfect clients, Frodo, Sam, Mae, Kishka, Quiche, Charlie, Belle, Guy, Dave and Star for generously donating their best poses for the creation of this page.